interviews

#13 sarathy korwar

Sarathy Korwar is a US-born, Indian-raised, London-based drummer, percussionist, composer and bandleader. He works predominantly in a jazz and Indo-jazz field but also incorporates elements of hip-hop, and other fusions. We chat about the meaning of futurism as it relates to being South Asian, the need to get away from 2 dimensional discussions around topics like race and what's keeping him inspired during lockdown as he drops a new record later this year.

Q1: How did futurism first become a fixture within your compositions and body of work?

Futurism isn't something that I've thought about in great detail in the past. Most of my work has dealt with the past. If you're talking about my first album with the Siddi community in India: looking at this community of people who have such a unique and interesting history and tracing that into the present to see who they really are. "More Arriving" is more of a snapshot of what it might be like to be a South Asian in the UK right now or even just being brown in different parts of the world. All people from different places just talking about what their realities are. For me, going from there - the question was "what do I do now? What can my next album be about?". Though the course of the interviews and all the questions I got asked around "More Arriving" and essentially all the questions I get asked around my work at some point - it's always "speak on representation, speak on race, speak on identity, speak on culture.". By now, I'm so sick and tired of talking about this stuff that I basically got to a catch 22 where you're making music that you don't want to represent anyone else but yourself and your whole point of making this point is almost "being South Asian in the UK is no singular experience" but you end up back just talking about the same things. You're kind of at the same time deifying yourself while saying that we need change. All I end up talking about is race and identity - no one's ever asked me what my hobbies are or what I'm into. There's almost no way to humanise oneself because we're facing this dehumanisation of minorities. Unless you get to connect on levels other than what you think structural racism is, you can't get past that. I started thinking about what a future that was devoid of questions around race, migration or diaspora could look like so I could start talking about things that really matter to me. There's a quote from Toni Morrison that "The function, the very serious function of racism is distraction." and I'm coming back to that quote a lot. Someone tells you don't have any culture so you spend 10 years proving that you have culture. Someone says you don't have any music so you spend 10 years working on music. Having to prove constantly who you are prevents you from doing the real work that you might be interested in doing. What would James Baldwin or Toni Morrison have written about if they didn't have to deal with race all the time?

Q2: Do you think the late capitalism is in focus due to the pandemic and the way it relates to south asians?

You almost forget what you actually like because you're not used to talking about it. Late Capitalism pigeonholes us all as creatives in any field. We're all trying to deal with the competitive nature of the business. It's never going to be conducive to any kind of real art. I think that the problem that we're in is that we have to choose to be "one thing". Specialisation is this forefront of progress. It's like a factory line where someone's only job is to watch over the screws that keep your laptop stand working. Are you a musician? Are you a writer? Are you a thinker? You can't be all these things. Oh you're into South Asian music? You can't also be into Jazz, that doesn't work. We need to focus this narrative into something that sells. That's what we're up against - that no one's willing to look at us in a nuanced way.

Q3: What are your hobbies out with music?

I play a lot of sports. I play a lot of tennis and watch a lot of cricket and football. Sports for me is my escapism. I represented my state in India in tennis when I was 16 - I was pretty serious about being a tennis player. I'm slowly coming back to it now after 10-15 years.

““A lot of the talk on futures and futurism relies on a certain kind of classicism. If somebody without class privilege from India was to express his version of the future we might dismiss it but then if someone from Kings College were to talk about it, it’s suddenly to be taken seriously.””

Q4: do your hobbies outside of music almost make it harder to "sell" you?

There's only one version of you that's going to sell. That version makes you appear one dimensional to everyone else even if that's not all of who you are. I can't not tackle race or representation because that's what affects me. If I don't talk about it - I'm doing myself a disservice.

Q5: Are we at a point where we can get away from this repetitive discussion of constructs like race or representation?

The sooner we can get away from constructs like race the better but we're not at a point where we don't have to talk about them right now or how they shape how unequal the world is: we need to talk about class, we need to talk about caste. Right now our attention has to be about bringing these things into sharp focus through our work.

Q6: What does Futurism mean to you and whose inspiring you right now in your upcoming work?

Reading stories have always inspired me. Be they in books or sports. When you're watching something like test cricket there are so many subplots and so many nuances to how things are playing out. There are multiple stories happening at the same time and these inspire me to do my own thing. Being able to dream of a world I'd like to live in keeps me going now. I read a great essay by Arundhati Roy from her last collection where says that "there's no going back from this" because what we were in was what caused this. The past has caused us to be messed up in the present. That's what has led us to this pandemic. I've also been thinking a lot about cyclicism and how it relates to how we talk about capitalism, how we talk about the end of the world. We're often stuck in this very Euro-centric idea of time functioning in a linear way instead of a circle. I feel like a lot of cultures, especially South Asian ones that think about time as circular. It feels arrogant to say that "time is going to stop at the end of capitalism or at the end of the world" as if there is a full stop. When I'm thinking about my next album and about futurism - I'm thinking about how the present relates to the past and how the future relates back to the past. Getting comfortable with this paradox that that doesn't fit within Eurocentric ways of thinking like "we don't know if humans made god or god made humans" when in many cultures - that acceptance is the norm.

I'm thinking about how I can decolonise my idea of the future. Even this idea of a "future utopia" is steeped in capitalism. So the "world is going to get better" but for whom is it going to get better, who needs it change and who envisions these new realities? A lot of the talk on futures and futurism relies on a certain kind of classicism. If somebody without class privilege from India was to express his version of the future we might dismiss it but then if someone from Kings College were to talk about it, it's suddenly to be taken seriously. It's a question of "who gets to imagine these futures". Who determines what is realistic is also tied up so much in ideas of class and coloniality.

#12 sarmistha talukdar

Sarmistha Talukdar is a Composer, Researcher & Film maker based in Richmond, Virginia whose work has been lauded by the likes of VICE, Wire Magazine & Bandcamp - releasing music under the name Tavishi. We chat about growing up with Indian folk music, using research techniques within composition and the differences between grassroots/academic music circles.

Q1. Your music often combines the sort of tunings found in Indian Classical music with more experimental sound textures. Can you pinpoint when you first became interested in sound art / sonic composition as forms of expression as opposed to more standard forms?

When I was pursuing my PhD in biotechnology, I had the privilege of learning Indian Classical music from the multi-instrumentalist composer and music director Mrityunjoy Mukherjee. I grew up exposed to classical music, Rabindra Sangeet, Nazrul Geeti and Bengali folk music. We lived in a rural part of West Bengal and we would often be visited by Bauls, or the traveling Bengali mystic musicians. A lot of people generalise the roots of my music as just Indian Classical music and I wanted to clarify that. Indian Classical music is beautiful and intricate, and it is usually more accessible to people of higher caste or upper class. However, there is a beauty and richness in folk music that has a delicate mystical quality and teaches people about being human. Bauls, who sing songs of transformation, are a socio-economically and politico-religiously marginalized cultural population from rural Bengal. A lot of Bauls were both hindu and muslim and their music had sufi and anti-casteist elements as well. Through their songs and narratives of emancipation, they question inequalities and injustices such as discrimination and intolerance (including class and caste hierarchies, and other forms of disparities) prevalent in the society. Their wise words and music had a huge influence on me.

Another kind of music that I grew up with a lot is Shyama Sangeet which were songs dedicated to the goddess Kali, whose origins can be traced to the deities of the rural villages, and tribal cultures. So I want to acknowledge the debt I have to the transformative art of marginalized people in India. In addition to these art forms, we would have a lot of art and cultural programs during different festivals and people would often perform Rabindra Sangeet or Nazrul Geeti. I was very privileged to learn Rabindra Sangeet when I was 10 years old. I composed some of my first songs in “standard forms” of composition then. My interest in composing sound art utilizing elements of drones, Indian classical and folk music and granular synthesis started with Tavishi in 2016. I started participating in experimental musical improvisation with my friends before Tavishi was formed, but in the same year. We formed a collective called Womajich Dialyseiz composed entirely of women, trans, non-binary and gender non-conforming artists. Improvisation with my friends started more as a way to not be confined by the rules of Indian classical music, share (safer) creative space and have more of a community-based approach to create art collectively. Thanks to the time I spent improvising with my friends, I felt more confident in pursuing my own solo sound art practice.

““I continued to use my molecular cancer stem cell research to generate sound art, and that was how my latest discovery on autophagy (literally meaning self eating, a cell survival strategy) was turned into a track called “I eat myself alive”, which was also an allegory for how QTBIPOC have to resort to either silencing themselves or use their trauma to be heard and survive.””

Q2.When did you first realise you could integrate elements of your scientific research into your compositions - e.g. on your 2017 release “Boundaries”? Can you expand on/guide us through the writing process typically for a composition where you integrate your research work?

So, when I started taking music lessons during my PhD days, my autistic brain started noticing mathematical patterns in them immediately. I brought it up to a male, more experienced friend who laughed at my idea. I could not believe that he didn’t see mathematical patterns in music, so I stubbornly would practice my instruments in between experiments in my lab, sometimes as late as 3 am. I noticed that I could generate music from algebraic equations and I wanted to explore that more, but I had to focus on finishing my dissertation and that had to be put on a pause. But when I started having the time after moving to US, I started delving more into how I could create art from data. In fact, the first Tavishi track ever was generated entirely out of data, and I was working on two different data sonification tracks almost at the same time. I was creating one of them using available image data of Pluto for a compilation dedicated to Pluto, its loss of planet stature and the New Horizons odyssey. Around the same time I completed one of my studies on cancer stem cells, and discovered a new pathway that regulates them using protein molecules called MDA-9 and Notch. I started tinkering with idea of using DNA, RNA and amino acid sequences as some kind of code to generate sound notes. Thus, the track “Notch Signalling” pathway was born. I continued to use my molecular cancer stem cell research to generate sound art, and that was how my latest discovery on autophagy (literally meaning self eating, a cell survival strategy) was turned into a track called “I eat myself alive”, which was also an allegory for how QTBIPOC have to resort to either silencing themselves or use their trauma to be heard and survive. Another track called “Not all struggles are visible” is also a data sonification track from my research which is about how queer and disabled people of color are often added as an afterthought, as if they are almost invisible.

Q3. Your latest release “Voices in my head” came out on London label Chinabot who have a strong focus on Asian futurism on their releases. Is a narrative understanding of your work important for any potential collaborators and did you see parallels between your own work and other releases on that label?

I am extremely honoured to be a part of the Chinabot family, I had strong reasons for being part of the label. Chinabot does amazing work for Asian artists, most of whom are experimental artists. The world of experimental music and sound art is very elitist, racist and centres on white expression. Asian artists have rich ancestral history of improvisation and sound art for before even any of the western names were born. Asian artists are pioneers of “noise” music. I found myself aligned with the values and work that labels Chinabot and Syrphe has been doing and I prefer to collaborate with people who share similar values. I have immense respect and awe for all the artists on Chinabot (as well as Syrphe) and I definitely see them all as artists confidently taking back the control of their narrative away from the white western gaze of what is sound art, what is experimental and what is avante-garde, in their own unique and powerful way. My art is and has always been political, and anti-colonial. And this also means being against Hindu nationalism, Brahmin supremacy and the ongoing colonization that India has been perpetrating in Kashmir.

Q4. Did making your first film feel like a natural progression from making audio - based art? Were there certain threads that you felt couldn’t be tackled within your work through sound alone?

A lot of people maybe don’t know about this but I used to be an avid creative writer as a child, I have written several original science fiction works, as well as mystery stories, and that is how I passed my English exams, which is very interesting to look back on. Story telling or narration is an important art form to me. I started painting a lot before I started composing music as a kid, I have in fact won several awards in state and national level visual arts competition. To me art and narration does not have clear medium boundaries, I think for me art is simultaneously visual, sonic, temporal, anti-temporal, and textural but in a very homogenous fluid solution kind of way where you cannot easily separate the molecules of one from the other but can taste them individually and collectively. Even with my first album I made music videos as part of the sound art, so making experimental short films seemed like a very natural thing to do. “HOME” was made as a way to express the important thoughts, concerns and voices of people around me, and as a way to process the complicated situation of navigating the idea of a home as an immigrant from a country that is still ravaged by colonization to a country that is currently a settler colonial state, while seeing the parallels of environmental racism in both as if they are still connected, as if the space-time fabric has convoluted into a timeline of knotted shape where the oppressive structures of white supremacy are connected to the ones being perpetrated here.

Q5. You’re an active member of the DIY scene in Richmond, can you comment on the freedom you have within DIY spaces to explore the identities inherent with your works versus more academic spaces for Experimental music?

In my limited experience academic spaces for experimental music are very rigid, elitist and racist. These spaces prioritize cis het white men who do not want to give up the space that they violently take up. These spaces minimize the work done by black and brown women and non-binary people. It often takes decades of relentless hard work to be noticed as an artist in the academic field. I have immense respect for artists like Dr. Yvette Janine Jackson, Madison Moore and Moor Mother, who have been tirelessly creating visionary art for a very long time. Vijay Iyer has been doing some great work as well. Academia takes its own time in noticing black and brown artists. The specialty of the (so-called) Richmond QTBIPOC DIY scene (not to be confused with other DIY scenes in Richmond which is as usual white and cis male centric) is its autonomic nature, and collective belief in building our own world. Collectives like Icecream support group, Great Dismal, Soft web, Womajich Dialyzeiz and Grimalkin are trying to build their own world, bottom up from scratch, not just artistically but along with grassroots organisations and mutual aid networks existing in Richmond and beyond. Their names might not be in mainstream media but their impact is felt deeply in the community and I am very honored to be part of this world building. We are all majority queer folks of color and when we work together, we don’t feel like our work is for capitalistic consumption of white heteronormativity. We work very hard to recognize and value each other. In contrast - in other spaces I often feel my work gets co-opted for the benefit of cis white people, particularly men. I remember once I performed an anti-colonial audiovisual piece in a reputed art gallery in New York. Apparently, my work inspired white male artist to speak up about his privilege (in his own words) and his entire piece was a monologue of how privileged he is as if it was a new found discovery and not something that has been prevalent since 1942 in the stolen lands of Turtle Island. The white majority audience lapped his work up, his work was “so progressive” but they refused to blindly see how much space his whiteness took up. If that is “contemporary art” then I do not want to be a part of such violent spaces. And so I have been avoiding them mostly. I did perform my anti-colonial piece last year in a recognized art museum consisting of mostly white people and it made them so uncomfortable that they left within 5 minutes. I felt as if my art had in some ways made an effort to decolonize the space literally.

Q6. Thanks so much for speaking with me. What releases can we expect from Tavishi in 2020/21?

Thank you for the conversation, I enjoyed it immensely! I also enjoy reading your interviews a lot, thank you for doing this kind of work. Along with your anti-casteist music, which are so important. I want to connect with all the artists highlighted in Desifuturism!! I have become friends with some already (shout out to Renu and Hamja, check out their work, it is so awesome!!) and I am really grateful for the connection. I am working on a collaborative project which will be called “Tavishi and friends”, as well as another short film, which has a lot of scientific and science fiction influence.

#11 Zarina Muhammad

Zarina Muhammad is an Artist, Writer, Art Critic and co creator of The White Pube. Her work has featured in The Guardian, Dazed & The Times. We chat about how she first got involved in art criticism and The White Pube, reflections on her piece about Diaspora Art and more below.

Q1. Your piece about Diaspora Art was one of the key inspirations for Desifuturism.com. What first drew you toward art criticism as a medium of expression and how did your site The White Pube first come about?

Gabrielle and I studied Fine Art at Central St Martins, and that’s where we met. As an art school, I think it radicalised us. There was just a culture there of speaking about, around and over art in a particular way that was a bit more politically coherent. Our course head said “CSM produces gobshites” and at the time we laughed, but like… it’s true!

We started The White Pube in October, 2015. Gab and I had this pre-existing relationship in the studio where we made work that was aligned with the same discourse, our practices ran parallel and we spoke about art and the work we made with like an insider’s confidence to each other. Gab recommended this show she’d just seen at a gallery nearby and gave me a bunch of reasons why she thought I’d like it, so I went along with her review of it in mind. It was anecdotal, word of mouth, friend-to-friend, but this recommendation had the value and weight of a review. On the bus back to the studio, I came across a review of it in the Evening Standard. I was fresh out the gallery with both of these reviews in front of me, and it was like I'd had a moment of clarity. The review from the newspaper was just describing what was in the room and then concluded with "...3 stars". Literally what does that mean!? I came back to the studio and slammed the review on the table, and we had this long discussion about how and why that review was bullshit - just giving the work an arbitrary rating. How it was just subjectivity masquerading as objectivity; and the idea that a critic can even ~speak objectively~ is bollocks because their objectivity in that situation is only ever a function of privilege - the idea that they have the authority to presume that their experience predicts yours. We decided to just write about art ourselves, that if there was a hole in the arts ecology that's not speaking to us, we should just fill this gap ourselves. It started very much as a joke you know! We didn’t realise it was a thing until people around us, that we respected, took it seriously. About 6 months in we were like, “oh shit, we’re art critics now lmao”.

Q2. Your point about the "binary juxtaposition" usually inherent with diaspora art really resonated with me as it's such a big hurdle for any diaspora artists I know whose work doesn't adhere to that trend. Your piece was the first I came across to articulate this. Do you think there's a reason for an aversion to discussing this common phenomenon?

The thing about the binary juxtaposition is, within the text it’s something I’m identifying as a damaging quality that undermines the work’s position and coherence, culturally, politically. It’s just one of those things though, where I’m more interested in where it comes from, and what causes it, rather than the fact of it as a descriptor, identifier or quality. Does it actually exist within the work as an intentional choice/strategy, or is complex and nuanced work flattened into this category by white curators in their drive to understand and simplify work by marginalised artists? A big part of that binary juxtaposition is that it comes from that feeling that you're consistently moving from a position of lack: that there's none of us, there’s no canon or context you can comfortably sit in, and that your work exists within a vacuum as a phenomenological novelty. My position as a critic has given me a really nice point to move from with regards to that, 4 years of being TWP has made me super aware that there are loads of us, a whole canon I was blissfully unaware of, and contemporary conversations for me to slot right on into.

When I wrote that text, I was thinking about artists outside of the formal pipeline of “the academy / the institution” makers being sucked in through these Tate Late, public-program moments that then becomes their main touch-point for reasoning and understanding of their own work. At the point artists of colour come into contact with the institution, there should be either a way to situate them into a wider canonical context, or adapt the institution to meet them and nurture them throughout this exchange. If they are these "new cohorts" in the way that the marketing copy suggests, there should be a way for the institutions to adapt to their presence that doesn't force them to assimilate into the pre-existing model, that’s just exploitative capitalistic extraction of their social capital. Maybe more institutions need to think about artist’s professional development and working with people on a longer-term scale, even in the case of public program, because there’s certainly very little there for artists at the moment, and it’s affecting more people than just Diaspora artists. After I wrote this piece I realised that it was a starting point and that I would be writing about it for the rest of my life.

““Diaspora Art could be considered outsider art - its practitioners typically don’t come out of art schools - so it could really be utilised as a medium through which working class Asian artists could crowbar access into the art world. But still, somehow the middle-classes are just everywhere?””

Q3. Do you think there's a denial of the correlation between SA artists often featured prominently and factors like Caste and class?

Yes! I think at the moment, the discourse around both caste and class in the UK is either like… outright denial of the fact that caste is a significant Thing that we need to discuss, it just get swept under the carpet, ignored and talked around or there’s just a bunch of upper-caste people standing around pointing out that no one’s talking about caste, saying ‘we need to talk about caste’. There’s a real vacuum in the UK, for some reason Dalit voices are just not being centred in this discourse, and none of us standing round pointing it out have the agency to fully dissect it with any actual sincerity or critical thought. None of us have the lived experience for that.

Upper caste South Asians have this proximity to whiteness and this access to power via historical, colonial structures that just isn’t unpacked in the way it urgently needs to be. There's an ongoing crisis in the art world where the overwhelming majority of people who end up here are middle-class, and Diaspora Art could be considered outsider art - its practitioners typically don’t come out of art schools - so it could really be utilised as a medium through which working class Asian artists could crowbar access into the art world. But still, somehow the middle-classes are just everywhere? All over it, it’s mad, the people with access to agency and ownership over their own narrative, with the cultural literacy to claim that agency over it, working with the big institutions, making big big bucks out of it are all middle-class. And then, because caste is so closely, tightly intertwined with class, it’s just this vicious circle that no one has analysed or dissected in a satisfying way. I don’t really know what to do about that other than complain about it to be honest, which is another problem in and of itself. It’s very stressful, I feel like I’m turning into a crank.

Q4. There's a running theme across all mediums (be it visual art, film, music) with regards to South Asian art that's the most visible - recognition seems most likely when there's a skewering of the most shallow Western perceptions of Indian tropes (i.e. the notion of one's art seeming Indian enough). Yet a lot of the most shallow art has a lot of support from the diaspora. Do you feel that South Asians in the diaspora have settled on the notion of shallow representation being better than none at all?

This whole perception that we have nothing there to represent us, in art, film, music, anything - it’s fully bollocks! We’ve been here, we’ve always been here, we’ve been making stuff for time, and there are whole histories for us to stand on the shoulders of. I think this politic of lack, it’s purposeful. The white institution forgets our contribution to it, and we never seem to have enough agency over our interactions with the institution to claim any kind of ownership to keep the records ourselves. We’re literally systematically kept out of accessing our own history; because it’s there, we exist within the art historical canon, it’s just not passed on or allowed to converge into the mainstream, and so it doesn’t spread or proliferate. Even now, we can see the pattern of it in action: it’s these white institutions that dictate the terms of these works, they can flatten nuanced work into that simplified binary juxtaposition by the way they situate them in context, churn them out as program in such rapid succession. From the Tate, to Nike or ASOS, whichever brands are funding or investing in these Diaspora works - criticality isn't actually important to them. If the work is simplified, graphic or flattened into an aesthetic-first conceptual weight, it’s optimised for Instagram and rapid circulation, which suits these brands and institutions best. They've opened up a new market to extract social capital from, that they can bolt their name to. It fits really well into this cynically commercial notion that representational politics is the end goal of diversity and inclusion, so these institutions don’t have to invest any time, labour or money into actually committing to change their fundamental shape, make up or operational practices. They manage to skate by just looking like they’re doing bits, they can co-opt this work into visible output that projects the image of change. It’s all on purpose, it suits the white institutions best, and we all need to be more cynical and wary of what we’re being roped into, what we’re being sold as radical. I know I sound like a fucking crank!

Q5. I started Desifuturism.com as a means to platform South Asian artists making genuinely interesting work outwith the cheap exotification inherent with capitalism. Are there issues you wish more SA artists were tackling in their work?

I don't think I'm too concerned about what I wish artists were tackling as much as the way artists are tackling it. I want a way more nuanced, critical approach; for artists to have more agency over the narratives around what they make, more ownership of the systems their work circulates in, and more alternatives and power in the interactions they have with these institutions. I want fair, liveable wages, more investment in our professional development and a fucking union, and anti-capitalist critique and BIPOC solidarity bc we share so many of our political considerations with black artists, and we need to be better at recognising our proximity to whiteness and power in specific situations.

Q6. Thanks so much for speaking with me! What can we expect from The White Pube in the near future?

Lots! More of the same! Just follow us on twitter and instagram, I never really know what’s going on until we’re doing it, but we’re always kicking up a fucking fuss with something or someone.

#10 Jyoti Nisha

Jyoti Nisha is a Director from Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh who is set to release her feature-length debut - a documentary film about famed jurist, economist, politician and social reformer B. R. Ambedkar in 2020. A work several years in the making - “B. R. Ambedkar Now and Then” is currently in post-production after a successful crowdfunding campaign. We speak about the politics of the Indian film industry, the influences behind her work and ability of the Bollywood film industry to address complex issues such as caste in mainstream cinema.

Q1. IN RESEARCHING YOUR WORK - I CAME ACROSS A FEATURE REGARDING THE NOTION OF BREAKING THE UPPER-CASTE “HEGEMONY” OVER WHO EXPLAINS AMBEDKAR. CAN YOU EXPLAIN HOW THIS CONCEPT RELATES TO THE AMBITIONS OF YOUR UPCOMING DOCUMENTARY FOR THOSE NOT FAMILIAR WITH THE POWER STRUCTURES AROUND CASTE-RELATED DISCOURSE?

Anybody can make a film on Babasaheb Ambedkar or say anything about him but what is “upper-caste hegemony”? It’s when people (of an upper-caste background) tell their stories from outside their own caste location minus any lived experience of the subject they are representing time and time again. A lot of times, when such people look into material which revolves around oppressed communities - there is a certain kind of distance. I’ve seen it in academia. It very interestingly tallies with the caste location of the person a lot of the time. It’s a type of gaze. While I don’t think that someone from a certain caste background cannot produce work which perhaps relates to race or gender or whatever - it differs if you’re born into it - it comes from actual lived experience. That’s what I felt when I started working on the film - Everyone is talking about Babasaheb but why? What are they saying about him? I felt like the image of Ambedkar has been confined within the category of him being a “constitution maker” or a “leader of Dalits” but he’s much more than that. I’ve seen this kind of reverence around him all my life when everyone from academia to politicians is making work about him but I don’t agree to that gaze where his followers can only be represented as “survivors” or “victims”.

““Babasaheb said that the emancipation of untouchables has to be brought by and for the untouchables themselves. Who’s going to lead the cause? If it’s your fight then you want to be the one leading the cause””

Q2. CASTEISM HAS SLOWLY BEGUN TO APPEAR MORE REGULARLY IN POP CULTURE - HOW DO YOU FEEL ABOUT THE CULTURAL INFLUENCE OF FILMS SUCH AS ARTICLE 15? IS IT POSSIBLE FOR THE BOLLYWOOD FILM INDUSTRY TO EVER TACKLE CASTEISM WITH THE NUANCE REQUIRED TO DISMANTLE IT PROPERLY?

I moderated this session with Media Rumble on the politics of cinema and we talked all about “Article 15”. The subject wasn’t just Article 15 but the politics of cinema. Somehow it revolved around Article 15. Several things were discussed and these points were already shared with the panel before. The areas of discussions were - caste as a discourse. Gender as a discourse. The trajectory of political messaging in cinema. Gaze in cinema and the significance and universality of a story. Article 15 was a problematic film for me - the way that upper-caste film makers represent caste stories and characters from marginalised communities has not been done in a very respectful way and they’ve just not given the characters the kind of dignity they deserve. Films I’ve seen have a very “Gandhian” approach to portraying anyone from a marginalised background - Gandhi didn’t do anything for scheduled castes or tribes. He was not anti-caste. He was pro caste. This goes back to films like “Sujata” where you have marginalised characters and you are talking about them but there is no solution - they’re just victims. In such stories - what has happened is that they have accepted as a notion that caste already exists in our society and around that - stories and characters have been created. You see these films and have to ask - where did this gaze come from and why does it exist? Why are characters from marginalised communities made to look a little dirtier or darker skinned (relative to other characters in the same film)? In Article 15 - I felt like that you didn’t need a Brahmin saviour. Babasaheb said that the emancipation of untouchables has to be brought by and for the untouchables themselves. Who's going to lead the cause? If it’s your fight then you want to be the one leading the cause. Article 15 was supporting the discourse of a “Brahmin saviour bringing about some kind of change in the society”. Caste is presented as a very serious problem but people are laughing about it in the film. People in the theatre were also laughing. The film doesn’t ask “why does caste exist?”. It merely tells us that it exists. Everybody already knows this. Even when it’s not very pronounced in behaviour - you can see it in terms of who you’re allowed to talk to or be married to. The film humanises its Brahmin characters so much by the end - all I could say was “The writing is bad. The direction is bad as far as the anything about caste has been represented”. There’s a scene in the film with a manual scavenger for which they hired someone who does that in real life but you don’t empathise with that character - you feel pity for him. Why are you showing me this guy coming out of a hole? One of my friends said that the film was “victim porn” because of how removed it was from addressing the right questions and how it was capitalising on discourse that’s popular right now which is caste.

Q3. I'M WORKING ON A PIECE ABOUT GATEKEEPING WITHIN INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSIC. OFTEN - AS IT TENDS TO BE UPPER CASTE INDIANS WHO HAVE THE CAPITAL TO LEAVE INDIA, THEIR CULTURE TENDS TO BE THOUGHT OF AS REPRESENTATIVE OF ALL INDIAN CULTURE - FOR EXAMPLE CARNATIC MUSIC. DO YOU FEEL THIS IS ALSO THE CASE FOR THE FILM CULTURE USUALLY THOUGHT TO BE REPRESENTATIVE OF INDIA?

When I was researching my Masters degree - there was this methodology we studied called “Political Discourse Analysis” where you would study discourse structure versus the power structure. Who holds the power here? Obviously upper-caste Indians and that plays a part in what films are sent by panels here from India to film festivals. I’ve lived in mixed communities before with people outside of India and there seems to be this homogenous view of mainstream Indian cinema and its relationship to Hinduism where India is this place of spirituality which doesn’t exist in The West. However - Independent film exists here. Over the last few years you have filmmakers such as Nagraj Manjule whose films actually address something. His films such as “Fandry” and “Sairat” don’t talk about issues like caste overtly but reference them thematically. There are also films such as “Kaala” and “Kabali” by filmmaker Pa. Ranjith which have assertive nuances and the characters have dignity and respect. At the end of it - with whatever film you see or news you hear - there is a whole mechanism behind it that has to connect with the ideology of the state.

Q4. IN FIELDS LIKE CARNATIC MUSIC - THERE ARE VISIBLE BARRIERS TO THOSE BEYOND A CASTE THRESHOLD BEING ALLOWED TO BE TAUGHT IT OR TAKE PART. MY RESEARCH REVEALS THAT OFTEN THE ROLES IN FRONT OF THE CAMERA AND BEHIND ARE DETERMINED BY CASTE. DOES THIS PARALLEL YOUR OWN EXPERIENCES WITHIN THE FILM INDUSTRY?

Yeah, one could say that but I’ve not seen it so much because I’ve not worked with mainstream cinema. People who work in the industry don’t tend to discuss their caste. Bollywood - is a money-maintained industry so nobody really takes any extreme positions. I’ve not seen it.

Q5. WHAT FILMMAKERS / FILMS THAT INFLUENCE YOUR WORK STYLISTICALLY OR STRUCTURALLY?

I really admire Aabbas Kiarostami, Krzysztof Kieślowski, Christopher Nolan and the documentary filmmaker Johan Söderberg - I’ve never seen films like that! Really amazing. His film “Lucky People Center International” totally blew me away and I’ve seen it several times.

#9 LAL

Rosina Kazi and Nicholas Murray are LAL, a Toronto-based protest electronic duo whose work draws on Hip Hop, Punk, Electronic and Experimental music. In addition to prolific community work in their native Canada and tours of Europe and America - They have collaborated with State of Bengal and members of Asian Dub Foundation. I speak with them about what drives the narratives within their writing, the artists that inspire them and what could be improved within the SA diaspora scene.

Q1. In researching your work I came across an interview in which you spoke of “Struggles in storytelling” and how that defines your ambitions as a band - can you expand on how this concept drives the narrative and sonic decisions within LAL

We have been addressing issues around race, sexuality and gender for the last 15-20 years. A lot of stories from the communities that we’re from aren’t really talked about in the mainstream so we centre that in our music. The awareness around Electronic music in Canada isn’t like how it is in the UK or US - the fact that our music is political as well makes it even more complicated. The idea of a “model minority” is really big in Canada - you’re coming from somewhere else while not wanting to upset the stereotype of being a “nice immigrant” who wants a house in the suburbs. It’s based on fear. A lot of South Asian artists in the diaspora are either contained within their own culture or mimicking something else. Rarely are we seeing people creating their own sounds. When we channel our own heritage in our music it tends not to be in a traditional way.

Q2. I first came across your work in a collaboration with Renu Hossain on her record “They Dance In The Dark”. How did you first meet and end up collaborating?

We met Renu through Sam from State of Bengal - We had just moved to London and she was already playing with him. I worked with Sam for years - he was one of the only folks from the Asian Underground scene who actually wanted to connect and work on stuff with us which was really amazing because I caught the tail end of that scene and was really inspired by it. We all toured together with Sam and became good friends.

““...it’s only when some of them started to make money that things really started to change. That’s when the egos took over. That’s when you start to see how capitalism can really divide us. “”

Q3. My conversations with Dr Das of Asian Dub Foundation & renu shared a disdain for a lot of the bigotry that went unchecked within the Asian Underground scene in its heyday. Rosina - Do your experiences with the scene reflect these experiences of claiming to fight one type of bigotry while holding another close to your chest?

Oh for sure, but I think that’s the case across the entire music industry. The difference I noticed from outside the Asian Underground was that originally these folks were coming together to create their own world and it’s only when some of them started to make money that things really started to change. That’s when the egos took over. That’s when you start to see how capitalism can really divide us. When I think of women or queer folks’ involvement in that scene - they were usually only backing vocalists or helping out with the promotion. They weren’t highlighted or up in-front. I think that was always there but then as the scene started to get acknowledged - even though a lot of work that got it noticed in the first place was collaborative - it became more and more toxic. Despite being someone whose been in the music scene for 20+ years, I wasn’t able to connect with anyone in that scene except for Sam and that to me says something. I find that people often get too caught up in the industry and forget about the ecosystem that they started from.

Q4. Are there parallels to be found between those problems in the Asian underground and the modern diaspora scene in Canada?

It’s interesting - we’ll check anyone out regardless of genre if they’re doing something interesting but not everyone is like that. Here - I feel like it’s segregated by scene. If you’re part of the Techno scene or Indie Rock scene or even the Bhangra scene - it’s all very segregated by sound. We’ll know all the weirdos from each scene but they won’t know each other. The weird thing about the Canadian diaspora is that a lot of the artists from here that we know had to go to Europe or America to really make it. There’s not a lot of artist development here.

Q5. Are there Canadian diaspora artists whose work you admire that you’d recommend for those not as unaware of the scene in Canada?

We run a venue ourselves so we have so many different artists come by. From a local perspective - we’re really feeling Yamantaka // Sonic Titan - they combine Metal & Math Rock with East Asian influences. Mixing a lot of shit together. They don’t get that the props that they should. In terms of people who are doing big community activism and creating their own worlds - Witch Prophet is also worth checking out.

Q6. Thanks so much for speaking with me! Can you tell me more about your upcoming release and tour dates?

We released “Dark Beings” in May 2019. The album reflects on our connection to the earth, the ground, the grassroots and is a continuation of our last album “Find Safety”. Right now we’re working on a US tour for March 2020. We just finished a Canadian tour. We’re looking at coming to Europe in February. We’re really keen to investigate what’s happening in Europe - there are a lot of radical spaces that we connected with on our last tour there.

#8 Amirtha Kidambi

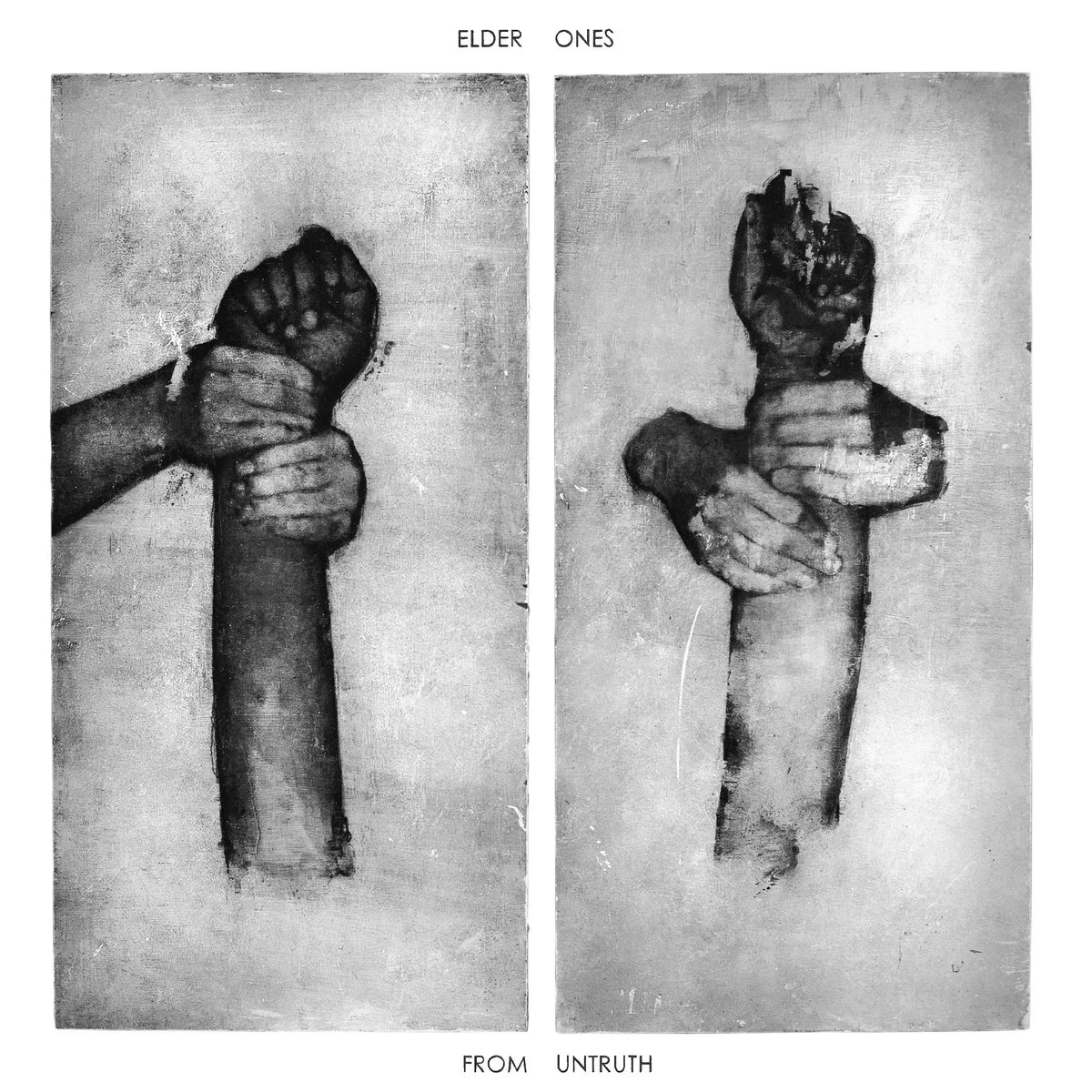

Amirtha Kidambi is a Vocalist and Bandleader who has worked with Mary Halvorson & Darius Jones, hosted a residency for Roulette.org and lead a number of groups including Elder Ones who released the lauded “From Untruth” in March 2019. We talk about navigating the experimental music press, South Indian identity in the diaspora and the growing popularity of Carnatic music in the American jazz scene.

Q1. How did your study of Carnatic music influence the most recent release of your band “Elder Ones”?

Something I always have to clarify for most of the population that talks about my music is that while I grew up around South Indian classical music (I’m named after a raga) - where my family lived in San Jose was much closer to a dance teacher so what I studied growing up was Bharatanatyam dance. My family were Sai Baba devotees and we sang bhajans often so I was immersed in that Indian folk tradition but I never really studied Carnatic vocal music until I was an adult. Most of my formal training is in Western classical voice but I already had a lot of the rhythmic language you develop as a dancer following the mridangam player. You learn it through your feet. A lot of the South Indian kids who grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area, Houston area or Queens grew up learning Carnatic music from a young age. There are so many people around who can teach it. It’s part of how Indian identity formation here in the American diaspora works - You have this emphasis on “having to do something Indian”.

It’s only in the past 7 or so years that I’ve started studying it with somebody and then I did a grant in India where I spent a full summer studying with a guru there. I know I’m never going to be a Carnatic virtuoso but I don’t really care about that. I want to be connected to that tradition that holds a huge place in my upbringing. I allow that influence to enter my music but I don’t explicitly sit down to write that style. I’m not a very deliberate composer. I wasn’t trained in composition - everything I know about it comes from a very intuitive place. I don’t even write anything on the page until I’m pretty far along in the concept. It’s way down the line when I notate anything. I compose by improvising - I sing and look for patterns developing and I make a lot of recordings. I flesh it out over a long period of time just improvising different ideas. Usually where the formal composition process comes in is where I’m actually fleshing out the form - figuring out how to transition from one big idea to another. The reason why I think the influence of Carnatic music is pretty obvious in any of the things I’m doing is because I’m approaching it from that improvisational-vocal standpoint. Carnatic music features a lot of subtractive and additive rhythmic formulae. Sometimes in a piece I’ll want to include that sort of idea in a specific part of a piece. Generally though - I try not to be that deliberate because it’s not my style.

Q2. In the UK there’s an erasure of South Indian identity due to the dominance of North Indian culture - are there similar parallels to this dynamic in the U.S?

It’s definitely the dominant culture that’s disseminated from India in the states because it’s had such a long history here that began in the 1960s but in the past fifteen or so years there’s been a lot more interest in Carnatic music in the jazz community thanks to people like Vijay Iyer and Rudresh Mahanthappa who are now educators. Vijay is at Harvard and Rudresh is at Princeton. My mind was completely blown when I found out about them as a junior in college in my undergrad in L.A. I heard their duo “Raw Materials” and was completely in shock. It doesn’t seem that long ago - it was 2004 or 5 but so much has changed. I landed in New York and immediately went out to see Vijay Iyer play and connected with him. He’s very much a mentor to the next generation of musicians.

A lot of jazz musicians now go abroad to study in India and what they usually study is Carnatic music. Wesleyan which has a close proximity to New York (where Anthony Braxton taught) had one of the first Carnatic programs in the country. There was a guy named John B. Higgins who became famous for his faithful interpretations of Carnatic music and he started the program at Wesleyan. A lot of the figures in the jazz scene here took a bunch of semesters in Carnatic voice. Somehow in this scene it’s become very visible. There’s an artist named Ganavya Doraiswamy with a record where she sings the jazz standard “Summertime” in Tamil.

Q3. My chat with Producer Kindness touched on the difference between who could migrate to the U.S and who couldn’t. It was initially mostly those of upper-caste background who were able to do so. In the South of India - Carnatic music seems predominantly enjoyed by upper-caste Indians but activists like T.M Krishna are working to correct this imbalance. Is this also the case with the way Carnatic music is enjoyed in the U.S?

I spent some time with T.M Krishna in 2017 when I was in India but I’m not so knowledgeable about who the audiences are at Carnatic concerts. When I was growing up in the Bay Area, the diaspora community you’d see were Brahmin because of who was able to immigrate. Here in New York - I don’t really get out to New Jersey much which is really where the majority of the community is on the East coast. When I see concerts in the city, the audiences are primarily westerners or Indian people who are also musicians. The Indian friends I have are all other artists.

When I was in India in 2017 taking Carnatic lessons - I was meeting Indian artists who were not Carnatic musicians which was very new to me - people like indie producers / hip hop artists who all view Carnatic music as this very classist form of expression even though some of them had studied it themselves. Some of them connected it to Hindu Nationalism. A lot of what I’ve learned about caste was through talking to them - caste appears very differently when you’re not at the top of the racial caste system here in the U.S.

““No matter what I say about my own music it’s often just labelled “Carnatic Music”. You have to correct the narrative. I draw very heavily on the AACM idea of “creative music” - if you use that term then there’s all this history of taking that power back and I really align myself with these musicians””

Q4. In my research of your work I noted you calling out a piece about you in The Wire that incorrectly attributed your origin to Brooklyn Raga Massive. Do you feel that the notion of “gatekeepers” within experimental and avant garde music spaces present similar struggles with those found in more mainstream music circles?

The systemic issues are pretty much the same across the board. You would think that maybe people in experimental or avant-garde music would be more well-read or more nuanced but that’s just not true. The people in the scene toward the critical or writing end tend to usually be older white men. My main project Elder Ones is in the jazz world and it’s systemically and academically become a very white scene. Like if Anthony Braxton wrote a 3 hour opera - it would be labelled jazz. If he did a graphic score, people would still call it jazz. No matter what I say about my own music it’s often just labelled “Carnatic Music”. You have to correct the narrative. I draw very heavily on the AACM idea of “creative music” - if you use that term then there’s all this history of taking that power back and I really align myself with these musicians.

The Wire piece was frustrating on so many levels. I took note of the fact that it’s a UK magazine but that didn’t excuse that they wrote about my music together with Rajna Swaminathan - our music is very different. We are associated only in that we are friends - we’ve never collaborated or made music together. I’m not offended but it’s lazy to conflate us like that. It’s so frustrating when this is the main experimental music magazine in the world - you want that big article, you want feature with a photo. The Wire has such a huge influence on promoters and curators - maybe someone would read it thinking my music is “world music jazz” and not consider me for their noise festival when my music is really harsh sounding. It was like “It would be a bad career move to burn this bridge” but I just had to get my point across. Not only did they group me in with this other artist just for the sake of a neat little narrative about the New York scene - in order to have this cohesive idea of that scene they brought in this group who I have a lot of tension with as they’ve policed what the idea of an “Indian musician in the diaspora” is. The article really mis-characterised the scene I was actually a part of which was the experimental New York DIY scene. I’ve played basements shows and studied Western classical music.

I didn’t want to say “Colonialism” with a Capital “C” right off the bat - I wanted to see where this came from and I gave the reviewer the opportunity to answer that question but essentially what he said was “I researched it and you are associated with them”. One Google hit does not a thesis make. I didn’t want to just do a call out because I wanted something productive to happen. It wasn’t until I wrote back with phrases like “ethnic grouping” and “colonial bias” that they responded with a proper apology and gave me an opportunity to publish my letter. I realised that I cared more about saying it than about what the repercussions of saying it were.

Q5. My conversation with Percussionist / Composer Renu Hossain illuminated the notion of a “protest record” not being sonically limited to the sound of “one person with an acoustic guitar” as often perceived. Would you define “From Untruth” as a protest record?

I guess because it was reacting to a specific situation. The election happened in late 2016 and I started writing “From Untruth” in early 2017. “Decolonize The Mind” was written when the Muslim ban was happening. I had just gone to a bunch of protests. “Eat The Rich” was written just as I was mulling over this capitalist nightmare that someone like Donald Trump was being propped up by these Republicans in exchange for tax cuts. I was thinking a lot about the idea of “techno-utopians” and how people like Elon Musk have this narrative that technology will save us when it really won’t. I had written protest music before - there’s a song on my previous record about Eric Garner. “Dance Of The Subaltern” came about from reading post-colonial theory at Columbia about these bigger issues. The biggest thing for me was that I didn’t write lyrics on my last record - there was this freedom to be really abstract but still have an ethos. “Holy Science” is somewhere in between the personal, the spiritual and the political. So is “From Untruth”.

I tried to take these things that I was thinking about and condense them into one or two lines of lyrics. It just felt like I just had to say something. I think back to Nina Simone’s quote that the artist has a “responsibility to speak out”. If you have skin in the game - it’s almost like you have no choice.

#7 Hamja Ahsan

Hamja Ahsan is an award winning writer, artist, curator and activist. We talk about touring the world with his innovative and vital book “Shy Radicals”, winning the Grand Prize at the Ljubljana Biennial and the works that inspire him.

Q1. Your book Shy Radicals: Antisystemic Politics of the Militant Introvert illuminates a type of intersectionality that's not talked about enough - especially in activist spaces that otherwise claim to be as inclusive as possible. Can you comment on this?

Just before Media Diversified (in my opinion, the most important online hub for conversations around intersectionality) stopped running I made a pitch to write an article for them called "Should quiet, shy, neurodivergent people be considered part of the intersectional movement?". But as the website ceased to run, it was never published. I actually miss the conversations there, I miss writing for them regularly. I hope it rises back from the dead as it’s a much needed space. I would be still be up for finishing this article if an editor out there wants it. Thinking about extrovert-supremacism is about the politics of listening and speaking, rather than just another added “ism” or “phobia” category of marginalisation. It’s a systemic critique of the hollow nature of capitalist liberal democracy where unrepresentative politicians are like used car salesman.

When I see Piers Morgan and Ash Sarkar from Novara Media arguing on daytime TV I do not see them as fundamental ideological enemies, but rather two wings of the same bird. They are both loud mouthed, over confident, brash, chauvinists, extrovert-supremacists. Consider the presentation style of Aaron Bastani on Novara Media - like a lad on the town, headbutt, gym selfie style. That is the ideology of who cuts it into the mainstream and monopoly of attention in social media. More insightful voices such as the radical human rights lawyer Gareth Peirce (my no 1 hero who represented my brother Talha) have a totally different mode of subdued communication which is in fact a break from media loudness, headline-grabbing and hysteria and panics. They will never be totally acquiescent with mainstream audiences, until a major structural change. So I don’t relate to the extrovert-supremacist media class but see them as walking over me and my peoples.

I notice this a lot in activist spaces I frequent in London and New York which are similarly extrovert-normative. When I spoke at a NUS Black Student campaign event, I heard the buzzword intersectionality in the air all the time, but all the election candidates would be hardcore extroverts: my peoples way of being wasn’t recognised. Not everyone wants to go to an aftershow party, not everyone thinks of mandatory clubbing as inherently emancipatory but more like an experience of exclusion, coercive jollity and dread.

I find that people who talk so much about equality and so-called diversity and access don’t consider this quiet mode of being as a key form of access. Even when people have birthday parties they gear it exclusively for their extrovert clubbing friends and don’t consider us quiet peoples with the same parity. So I have birthday sit-ins instead and think-ins in galleries to open up that space that the subaltern republic. I feel affirmed to these the recent spread of #toxicpositivity being recognised too, the invalidating, obnoxious, victim-blaming inherent in so-called "positive thinking". I feel its part of the same wave.

The rise of Greta Thunberg has been such a breath of fresh air for me and I relate to her more than any brown media personality. She's the best person in the mainstream media since Lisa Simpson and the neurotypical-supremacist attacks on her by the Brexit brigade and wokey mob deeply disgust me. In my global lecture series and touring around the book I trace the historical legacy of introvert radicals who changed the world from Clement Attlee bringing us the welfare state in 1945 to Patrick Pearse, leader of the 1916 Easter Rising, the spark that inspired the end of European colonial empires.

Q2. You just won the Thirty-Third Ljubljana Biennial of Graphic Arts Grand Prize. How did it feel to win this award?

The Grand Prize came as a total shock to me. The award is given to what an International Jury consider the best artist in the biennial. I hadn’t been an exhibition-based artist for years due to full-time campaigning for my brother Talha Ahsan who was held without trial for 8 years and then extradited into solitary confinement in a death row prison in America by Theresa May. On top of that I had my own lifelong struggles with bipolar disorder and feelings of worthlessness and long-term unemployment. I had grown with a feeling of defeat and depression for many years since graduating from Central Saint Martins and considered permanently leaving the contemporary art world which I saw as a hollow neoliberal bubble for the 1%. I didn’t think people like me won awards.

The Ljubljana biennial was my return to being an exhibition based artist. I had a deep feeling of inferiority to everyone, especially Turner Prize nominees such as Lawrence Abu Hamden and Nicole Wermer were in the running. The other artists had been in Documenta and Venice Biennale, big public museum collections, the world over from China to Iran. I felt like a no one. Then when I beat all these guys, it felt kinda cool.

I looked at the previous winners of this Grand Prize and they included David Hockney, Damien Hirst, Robert Raschenberg and Joan Miro. I didn’t think I would ever win the award and considered going on an alternative underground walking tour of the city during the time of the opening award ceremony. The biennial staff just caught me by accident on my favourite narrow side street ( where Slovenia's only falafel restaurant and Bangladeshi takeaway is located) and then told me like less than an hour before the ceremony the good news and that they had been searching all over for me. They only recognised me as I happened to be wearing an official biennial name tag saying “Hamja Ahsan - Artist” on it. I liked wearing these name tags as they made me feel like it was my official job and gave me free access to all the associated galleries in the biennial.

The award was for the work Aspergistan referendum which was a participatory artwork spread amongst 4 galleries of the biennale with ballot boxes and laws from the state, where the audience could vote to join the federation of Aspergistan - A fictional homeland nationstate for shy, quiet people I had made up in my book “Shy Radicals Anti-systemic Politics of the Militant Introvert”. It resonated with the Brexit crisis at home in Britain and within the state of Slovenia as the first state to leave the communist federation of Yugoslavia via a ballot box. I spent a lot of time wandering the Museum of Contemporary History during an earlier research trip and the ethnographic museum, the parliament and embassies. The wall text about “The State shall guarantee freedom from small talk” and “abolition of private views” and 24 hour access to public libraries resonated deeply with the quiet introverts amongst the Slovenes audiences too. According to the award jury, the call to vote in the Aspergistan referendum: "passionately engages the democratic voting process, demographic representation, national iconography and viewer engagement to question and potentially repair the wider structures of social exclusion and alienation. With his image of a “militant introvert”, Ahsan proposes a reparative social framework that is lucid, humorous, poetic and politically resonant".

Slavs and Tartars collective, the curators of the biennial, treated me with a lot of kindness and hospitality. They told the press preview what a fantastic book “Shy Radicals” was and held up a copy to the camera. Payam Sharifi from the collective, from the Iranian diaspora, joked with me about how I had to convert to Shiism to get the award just before i got on stage. I told him about my hopeless crushes on revolutionary Shiite women when I was younger.

When I arrived at the award ceremony the entire regions TV, news and radio media were there at my feet. My name was broadcast on the hourly news and even my cab driver congratulated me and knew who I was. The news reports were cool, sensitive and well edited and I got a big feature in the largest left-wing newspaper in the region - DELO, popularising the #shypower salute (see instagram for that hashtag and it make sense). However going home was rather deflating as the British media didn’t really pick up on the story like the Balkans media did. I didn’t feel valued, recognised or respected. It reminded of the wilderness years of campaigning for my brother when no one wanted to know and I struggled so hard for press mention. There were lots of white British journalists there though - being wined and dined - however, none of them bothered to write any further despite being in the same room as me. Only a small column in Art Monthly. The British council however came to the award ceremony and did some nice tweets for me which was sweet.

I had a homecoming ceremony dinner in my hometown of Tooting - the South London area of South Asian high streets where the London Mayor Sadiq Khan was elected MP - at my favourite Pathan restaurant Namak Mandi with many of my long-term fans, readers, supporters present. People who ran Decolonising the Archive, Stuart Hall library, Tate were all present. This was organised by the artist Hassan Vawda who thought I deserved a hero’s homecoming.

So, all in all, the award was a phoenix from the ashes moment for my career as an artist. I also wanted to be an artist since I was 4 years old, so those wilderness years of defeat and despondency were like a form of suicide.

Q3. What first inspired you to begin this book - was it another work you read or was it your own experiences not being reflected in the current literature you came across?

The book was inspired by my experiences of primary and secondary school bullying for being quiet. People would hate on me for just being quiet. It couldn’t be recognised as a hate crime as such. Sometimes this came from other South Asians or other muslims or people from the same community as me. I wanted a Liberation movement, accountability or an collective identity that would protect me.

There is right now a mini cottage industry of introvert lit inspired by the commercial success of Susan Cain Quiet in the last few years. This is noticeable too in online meme culture and #introvert on instagram etc. I described her as "the Tony Blair" of introverts. I have mixed feeling on this. Some of it is quite good and relatable. But they take a view of being twee, cute and self-deprecating. Whereas I want to say this: I am Shy, don’t fuck with me.

The biggest influences on it is the book “Use Illness as a Weapon” by Socialist Patient Collective - a radical Guerilla psychotherapy group from the 1960s who used analogies from the Vietcong and Guerilla warfare. I use the term “extrovert-class” in my book after their term “doctor-class”. I was influenced by the formats of Black Panthers anthologies. I read a lot of political prisoner writing from the 1960s and Cointelpro era. I find prisoner writing very insightful, more so than official Postcolonial writing from academic institutions like Goldsmiths and SOAS which I find stale and formulaic. My brother Talha wrote some beautiful award-winning poetry in prison which inspired me. This was read and championed by the actor Riz Ahmed, comedian Aamer Rahman Jeff Mirza, and novelists and peers such as A. L Kennedy, Michael Rosen and Jackie Kay. Aamer Rahman even offered me to go on UK tour with him on the Fear of a Brown Planet gig and invited me on stage to speak about Talha’s cause.

I also read and reread books from the sixties revolutionary era such as Valerie Solaris SCUM Manifesto, the star of “I Shot Andy Warhol”. I been fascinated by her ever since I saw her quoted on Manic Street Preachers record sleeves as a teen. H Rap Brown works, also known as Jamil Al-Amin. Lots of radical underground literature from the 1960s that challenged the order of things. Today we just have long-form dry essays in a semi-academic style that come out on Verso or Pluto press as the standard form of leftist writing.

Autistic life writing had a big influence on the book too. I started to read this genre of writing when my brother Talha was diagnosed as being on the autistic spectrum. I have recently come across the work of a Bengali diaspora autistic writer Tito Rajarshi Mukhopadhyay whose memoir “How Can I Talk if My Lips don’t Move: Inside my autistic mind” really moved me to tears. Everyone should read this book. Shy Radicals also functions as a zine distro, so when I table at zine fairs around the world or radical book fairs I table and register as Shy Radicals. Mental Health fanzines like Icarus Project - an American bipoplar collective which wish to reclaim aspects of divergent experience also influence the book. I distro mental health zines and work with the radical mental health zine Asylum.

““People who have suffered like me growing up have written to me saying that having a critical lexicon to navigate the world was very empowering to understanding the pain, inequality and injustice they experience in the world as introverted people.””

Q4. When you started writing "Shy Radicals" did you envision it taking you to such accolades and have you noticed a mark change in the attitude to the notion of "extrovert supremacy" since you received it?

I didn’t envision or expect that much when the book came out: it took over 4 years to write when I was often very poor or depressed. What was most meaningful to me was how the book was adopted in educational institutions around the world as required reading. At Brown University, (an Ivy League university in USA with open curriculum) it is on a syllabus called “Neurodiversity, Science and Power” and taught alongside Octavia Butler and Steve Silberman. That means so much to me. It’s also taught at universities in the Netherlands, Germany, Belgium and even in Birmingham University in the UK where it is a project text for undergraduate artists. My book is now Bookworks best-selling title too and has gone into three editions in two years and an Italian translation coming out October 2019.

Out of all this touring and publicity, I do want the words and vocabulary to live on beyond me and beyond the book. I want people to identify “extrovert-supremacists” in their communities, their nations, their history, where ever in the world they may be... People who have suffered like me growing up have written to me saying that having a critical lexicon to navigate the world was very empowering to understanding the pain, inequality and injustice they experience in the world as introverted people.

Q5: Do you find you have to adapt your approach depending on the culture of the place you're presenting the book in? As How do you explain the book to someone whose perhaps unaware of the contrast between extroverts and introverts? Are there marked differences between say a South Asian diaspora absorbing the messages verses a white audience?

Other contemporary artists of the British South Asian diaspora, my peers in the art world, really supported me. As soon as the news was announced, the painter Matthew Krishanu, Hassan Vawda and the poet Azam Ashim texted and contacted me straight away saying I was an inspiration to them. I spoke a lot to the artist Jasleen Kaur when I was making and developing the commission proposal for counsel when I felt my mind was eating itself up, who was making a public art commission for the Baltic in Gateshead at the time. It was good having this support network. The artist Michelle Gamaker, from Sri Lankan diaspora, was also supportive towards me and with come to my public event like a loving desi aunty. Rehana Zaman wrote to me to say I deserved the award as it was an amazing book. All these peers of mine, British South Asian artist, some more successful than me, gave me advice and institutional support just out of kindness.

I could relate the Shy Radicals work to a previous art project I did called Redo Pakistan. It’s a nomadic art project based on a newspaper stall I did for a number of years that travelled South Asia, London and New York where I invited artists and writers to invent fictive solutions for the troubled nation of Pakistan. I made references to Jinnah, Muslim league, Allama Iqbal in this project and the contested historiography of partition. I also referenced Sadaat Hassan Manto (who I consider to be the greatest short story writer of all time). I talked about the difference in the introvert sensibility of Satyajt Ray World of Apu films and Punjabi Dhol drums and bhangra which was also lost on white audiences. I find white British people are astoundingly ignorant of the basics of colonial history. Most have never heard of the 1943 Bengal Famine which starved to death 4 million Bengalis and instead deify the racist Imperialist Winston Churchill. Even the basics of Irish history is lost on the average white British person. A systemic nation effort must be made to readdress this and its long overdue.

However, the book has a pan-shy appeal where people from so many disparate nationalities from West Africa to East Asia connect with the book. That’s the point of the book - how there’s this class of people beyond national borders who need to unite and overthrow the “Extrovert World Order”. I have discovered this on my ongoing world tours. So it’s not between a brown audience and a white audience but an introvert audience and an extrovert audience. I find introverts know they are introverts through a common experience of bullying at school, the workplace or public social places where they are made to feel like they don’t belong.

#6 RENU

Composer / Producer / Percussionist Renu Hossain began her musical journey around 2000. Originally a percussionist for artists such as Grace Jones and bands in the latter part of the Asian Underground, she started to produce her own music in 2010. We talk about session work, releasing an album of avant electronica and collaborating with deceased vocalists.

Q1. Your career includes session work with artists such as Grace Jones, Tunde Jegede and Fun-Da-Mental. Was working as a solo artist always a goal of yours or did that develop over time while you were working as a percussionist for other people?

In the beginning all I wanted to be was a session percussionist. I was blinded by the big stages. You can get good money for it too. However, if you’re not a follower and more of a rebel with your own story - that’s not really going to work for you? At the time I just didn’t have the guts or the skills to become a solo artist. I really enjoy accompanying people but it’s very infrequent now. Nowadays it has to be something Classical when I do it. I’m working on accompanying Indian Classical musicians now with my mentor in Berlin. Indian Classical music is really difficult, just the maths of it. But it excites me in a way that other music doesn’t. I don’t want to play 4/4 or 6/8. I don’t want to accompany a singer anymore in that pop context either. I decided I wanted to be out of the sidelines and up front - but on my own terms.

Q2. Your most recent LP “They Dance In The Dark” is such a fascinating record - not least because it’s quite a departure from your previous work. How did working on your previous records bring you to this point where you wanted to get away from a background steeped in Indian Classical & acoustic percussion and make a record so electronic and dance-focused?

I’d actually released 3 albums before that one. The first album was called “Love From London” which was me playing around on the guitar and writing songs. Stylistically - it’s a nod towards the sixties. It’s got a musical theatre vibe about it and it’s a bit tongue-in-cheek. I used to play guitar and write in the evenings just because I was playing percussion all day while doing session work and I wanted to relax. My second record has more Psychedelic & Latin vibes to it. I was playing with a lot of Peruvian and Bolivian bands at the time. It’s called “Midnight Radio” and I’m still really proud of that album. The third album was very experimental. It had me starting with electronic sounds but they were very subtle. I was working with a choreographer who was an ex-practising Christian so I channeled her stories and her vibe. I was reading about Hildegard and christian cosmology. I was looking into the concept of someone following something dogmatically. “They Dance In The Dark” was me trying to see if I could work it “within the box”. Just me and my computer. No outside musicians like with the other three albums.

Q3. I note there are a couple of collaborative efforts on your LP. Where they do appear - they add a really interesting dimension to the songs. How did you go about choosing your collaborators and guests for this record like the poetry heard on “Queen of Heaven”

What happened there was - most of the music was already made and I chose singers who had something to say themselves. There’s an amazing singer on two tracks called Rioghnach Connolly who I think is gonna be BBC folk artist of the year. A lot of the artists I chose are breaking through - they’ve been around for years but they’re finally gaining notoriety in their own countries. The track ‘Salma’ features a singer called Sandy Chamoun is big in Lebanon. It’s based on an old Iraqi folk tune she sings that looks back at a time before the present-day politics of the Middle East. When I first moved from London to Berlin it was just as Refugees Welcome Movement had taken off. I met all many asylum seekers - the majority of them queer. “Queen of Heaven” features cut up excerpts from an interview with a trans asylum seeker from Iraq who I met in Berlin. In the interview she talks about how Arabic poetry often references the idea of “long black hair” as a sign of being a woman and how having long dark hair would let her attain femininity herself. She talks about how she used to be made fun of - people would say she “danced like a woman” but inside she’d feel so happy because that’s what she always wanted to be. The title of the track refers to Nin-nana and pre-Islamic Mesopotamian goddess - now the saint of trans people in Iraq.

Q4. “They Dance In The Dark” platforms the voices of many marginalised communities. Was there an element of having to unpack your privilege of having grown up in the west when working on the themes behind this record?